In the second part of our recession series, we meander through the Great Recession…from trough to peak and back to trough again. We focus on the “slow burn” – how long it took for the whole episode to unfold, how difficult it was to know when to start worrying, and how long it took after some major milestones for local tax revenues to really take a hit. If you want to peek back at part one, have at it!

From trough to peak

Following the dot-com bubble and the shock of September 11th, the national and regional economy found its footing. The recession that had followed the dot-com bubble was relatively shallow and brief. Certainly, there was a local impact, but generally that impact is (my choice!) beyond the scope of this piece. That said, I will note that it did lead to some changes to local tax policy in Mo Co: tripling of the Fuel/energy tax

From 2004 to 2006, the national economy was strong by most metrics: the national unemployment rate was consistently below the range that typically would have been considered “full employment; growth of income and output was generally in the range of 3% to 4% per year; inflation was generally “under control” and within a manageable range between 2% and 3% annually; and the S&P 500 returned 35%, or roughly 11% annually.

However, an asset bubble was building in the housing market. Fueled by cheap money and relaxed lending standards, too much debt was taken on by households and too much credit was issued by lenders. As an example, according to the Federal Reserve, household debt increased significantly, from roughly 85% of disposable income in 2000 to roughly 120% of disposable income in 2006. I am old enough to remember that during this period, many households took out home equity loans to pay for TVs. And, of course, investors and lenders financed construction of units for which there was no market demand and purchases by “flippers.”

- A September 2004 article in the New York Times summed up the froth: “In most parts of the country, people buy places because they want to live in them. But in markets where prices rise every month, flipping looks like an easy way to get rich.”

By mid-2005, it was evident that the housing market was driving the US economy. At that time, I was doing a lot of economic base analysis for planning and real estate market studies, and I remember realizing one day that almost all recent economic growth in jobs was attributable to housing. According to the US economic accounts, three industries – construction, finance, and real estate – accounted for 14% of US jobs in 2001 but accounted for 34% of US job growth from 2001 to 2007.

- A July 2005 article in the New York Times identified the problem without, per se, identifying how problematic it was: “The real estate industrial complex, the economic engine that has become one of the few reliable sources of growth in recent years…[encompasses] everything from land surveyors to general contractors to loan officers…has added 700,000 jobs to the nation’s payrolls over the last four years…”

Those national trends, of course, had local parallels. In Montgomery County, those same three industries referenced above – construction, finance, and real estate – accounted for nearly 17% of Mo Co jobs in 2001 but represented a whopping 40% of the County’s job growth from 2001 to 2007.

By October of 2006, it was evident that the national housing market had begun to cool. In late October of that year, the Commerce Department reported that the median price of new home had dropped nearly 10% from September 2005 to September 2006. By early 2007, it was evident that the nation was experiencing a sharp increase in the number of troubled real estate loans; a sharp drop in the Chinese stock market also contributed to negative sentiment. Through most of the early and middle part of the year, economic sentiment tracked the daily headlines – confident in the underlying strength of the economy when economic reports at home and abroad were positive; concerned about news of underperforming mortgage portfolios and the end of the housing bubble and the growing US trade deficit; and conflicted when either good or bad news seemed likely to have significant implications for Federal Reserve policy that could result in tightening credit or further froth.

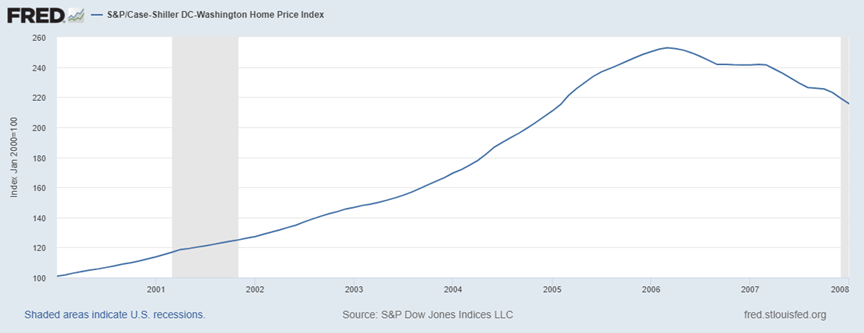

Specific local housing markets, including the DC-area market, concealed their cracks until somewhat later; in many cases, the cracks were obscured by steady prices but reduced demand or an increase in the average time on the market. In the greater DC region, home prices peaked in early 2006, though the initial decline was somewhat modest.

At the peak

In general, the metro region’s economy peaked in late 2007. Maryland’s unemployment rate reached a low of 3.3% in November of 2007; Montgomery County’s unemployment rate hit 2.4% one month later. During the first 10 months of the year, the S&P 500 climbed 9%. Keep in mind that housing prices had already started to fall.

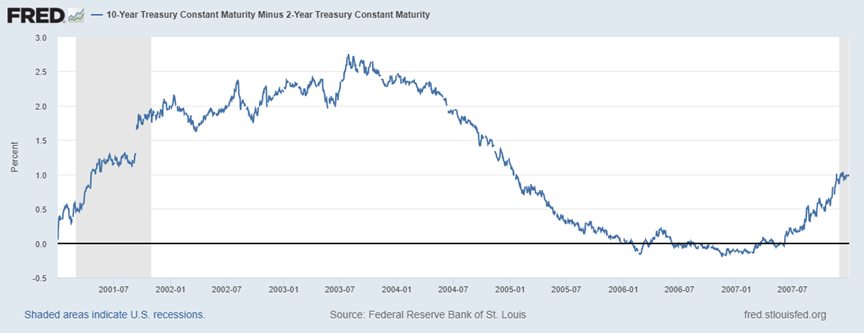

By that point, there had been some signs that a recession was coming. For example, the early 2006 inversion of the yields on 2-year and 10-year US government bonds was a sign of trouble ahead, though strength in the labor market gave folks pause and consumer sentiment remained generally positive. Household savings were falling, and lenders kept on lending.

For the County, real GDP was actually more or less stagnant in 2006 and 2007 (both somewhat lower than 2005). It jumped again in 2008, then fell slightly in 2009, as GDP in industries like real estate and finance joined construction, which had fallen somewhat earlier.

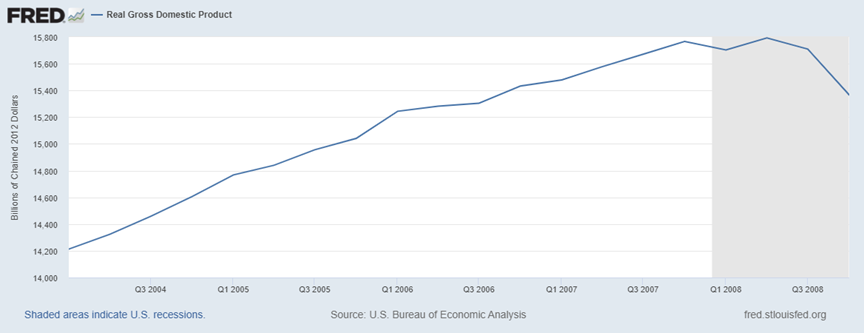

Real U.S. GDP peaked in Q2 of 2008. The typical “two consecutive quarters of real GDP decline” criteria had been met in the second half of 2008, though the NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee determined that the recession began in late 2007.

Furthermore, interest rates were on the rise. This reduced consumption because purchasing goods with credit became more expensive, and more importantly it resulted in increased debt service payments for those with variable rate debts, thereby reducing their disposable income. As spending slowed, incomes dropped, jobs were lost, and the downward spiral was underway.

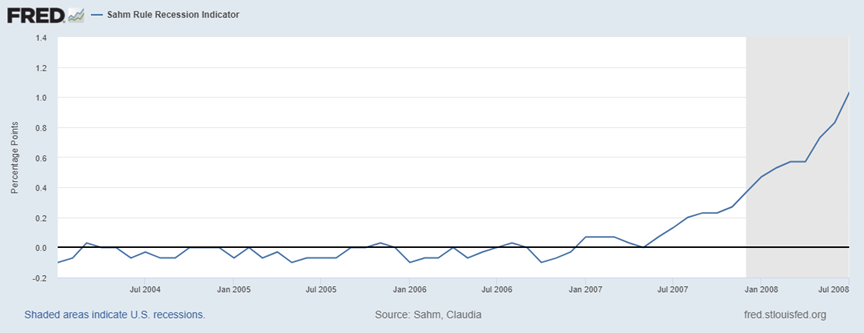

August 2007 was a particularly important turning point. BNP Paribas, the largest bank in France, froze $2.2 billion in assets that had been exposed to US subprime mortgages. Here at home, the nation’s largest mortgage lender, Countrywide, was at risk of bankruptcy. The Federal Reserve, in a rare emergency meeting, voted to cut interest rates by 0.5% to provide a lifeline to the financial markets, and made loans to large banks (including Bank of America, J.P. Morgan, and Citigroup) to facilitate the orderly functioning of the nation’s financial markets. That month, Ray Dalio, of Bridgewater, presciently declared “This Is the Big One.” It would take a few more months for that realization to spread, as most folks still believed that the problem was confined to the mortgage market. Remember how I said that the 2006 inversion of the yield curve wasn’t causing too much angst because of the strength in the labor market? Well…by the second half of 2007, economists were seeing trouble in the monthly labor market data. I discussed the so-called “Sahm rule” in my last post, and I’ll break that one out again. When the 3-month moving average unemployment rate rises to at least 0.5% above the low of the last 12-month period, this is often a sign that the economy is in recession.

During the years from 2001 to 2007, Mo Co gained nearly 52,000 jobs. While 2006 was not a particularly good year for the region’s economy, Mo Co resident employment in July 2007 (506,000) was slightly above July 2006 (504,000). Sure, the national and global financial plumbing had sprung some leaks, but on the ground in Mo Co…well, things appeared to be plodding along. The unemployment rates in Maryland and in Mo Co were very low (Maryland reached a low of 3.3% in November 2007, and Mo Co achieved its low of 2.4% one month later – in the first month of the recession).

Mo Co resident employment went higher yet, reaching 513,000 in July 2008. In many respects, that was not simply the end of the peak of the last economic expansion, but the end of the peak of Mo Co’s economic history. One year later, the number of employed Mo Co residents had dropped by more than 10,000.

The FY09 County budget, approved in May of 2008, was not an “end times” budget. Budgeted revenues for FY09 included overall local tax revenue at more than 8% above FY08 and total revenues at more than $207 million above FY08. The FY09 approved budget for Montgomery County Government was more than $260 million more than it had been in FY08. Total taxes and charges for the average household would increase by 6.5%, driven largely by an 11.4% increase in property tax burdens. But hey, with home values only down a little from the early 2006 peak, what could possibly go wrong?

Looking back at some of the budget documents, it looks like the good news was that the Executive and Council held the line on the size of agency workforces, which increased by only about 130 “work years,” or 0.4%. On the other hand, Montgomery County Government personnel costs increased by 4.1% in the FY09 approved budget, though it was approved after several broad economic indicators had turned negative.

And from peak to trough

From late 2007 into 2009, the stock market lost nearly $8 trillion in value, and household wealth declined by nearly $10 trillion as a result of the collapsing stock and housing markets. In June 2008 alone, the S&P 500 Index fell by 9%. The Fed faced some tough decisions, consumer confidence was plummeting, and oil prices were rising. “Too big to fail” was a phrase that we had only recently learned, and we were sick of hearing it already. On August 7, 2008, AIG reported a second quarter loss of $5 billion. It was becoming clear that what had started out as “simply” a problem in the housing market was much broader, and that it had actually exposed catastrophic problems in the plumbing of the financial system.

On September 15, 2008, I purchased a house. Others will remember that day because Lehman Brothers – at that time the nation’s fourth largest investment bank – collapsed. Remember AIG and their $5 billion Q2 loss? Well, by September 16, AIG was the recipient of an $85 billion rescue loan. One day later, a New York Times article captured the changing mood of America:

Financial Crisis Enters New Phase (By Vikas Bajaj, Sept. 17, 2008)

The financial crisis entered a potentially dangerous new phase on Wednesday when many credit markets stopped working normally as investors around the world frantically moved their money into the safest investments, like Treasury bills.

As a result, the cost of borrowing soared for many companies, while the stocks of Wall Street firms like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley that only a couple of weeks ago were considered relatively strong came under assault by waves of selling. Investors were so worried that they snapped up three-month Treasury bills with virtually no yield and they pushed gold to its biggest one-day gain in nearly 10 years. Stocks fell by nearly 5 percent in New York.

The stunning flight to safety, away from other kinds of debt as well as stocks, could cause serious damage to an already weakened economy by making it more expensive for businesses to finance their daily operations.

Some economists worry that a psychology of fear has gripped investors, not only in the United States but also in Europe and Asia. While investors’ decision to protect themselves may be perfectly rational, the crowd behavior could cause a downward spiral with broader ramifications.

“It’s like having a fire in a cinema,” said Hyun Song Shin, an economics professor at Princeton. “Everybody is rushing to the door. You are rushing to the door because everyone is rushing to the door. Clearly, as a collective action, it is a disaster.” …

At the end of FY09, Maryland’s unemployment rate had risen to 8.0% (June 2009). One month later (July 2009), the first month of FY10, Mo Co’s unemployment rate peaked at 7.9% and, as noted above, there were 10,000 fewer employed Mo Co residents than there had been the previous July. Nationally, unemployment peaked at 10% in October of 2009. Indeed, these were dark days.

In March of 2010, then County Executive Leggett transmitted a bill to suspend the routine allocation of a portion of the transfer and recordation tax revenue to specific funds, requesting that the Council divert the needed revenue to the General Fund for the next two years. During the Council’s review of the FY11 budgets, the County Executive was forced to submit multiple proposals to increase the Fuel/Energy Tax simply so that the County could maintain adequate liquidity as the fiscal year came to a close (in the end, the actions taken resulted in an energy tax that was roughly 10x the level it had been at prior to the 2001 recession). Mr. Leggett indicated that he would sunset the emergency increase in the tax after 3 years, but 3 years later the County’s revenue problems were still manifest, and Mr. Leggett did not recommend sunsetting the tax increase.

Moody’s placed Mo Co on a watchlist, citing the need “stabilize and replenish reserve levels and restore financial flexibility.” Reductions in force, furloughs, and retirement incentives were all on the table. This April 2010 memo from Steve Farber, the Council Staff Director, is an interesting time capsule for those who want to read more.

I won’t go through the rest of the crisis in a blow-by-blow manner. But I think it is important to highlight the slow burn that played out over the course of several years. There were many days during that time when it wasn’t entirely evident that history was happening. There were days, and even weeks, when the stock market went up. There were years in which the employment situation improved, and moments when policy solutions appeared promising. And at a local level, there were approved budgets and fiscal planning documents that anticipated a return to “normalcy.” No one knew, and no one really could know, that this was a recession from which we would spend years recovering.

Keep in mind, by the time the financial crisis had become a local budget crisis it was 4 YEARS (!) since the yield curve had inverted and since the Case-Shiller Home Price Index for the region had peaked. It had been 2 YEARS (!) since real GDP peaked and since the Sahm rule first indicated that unemployment had increased in a meaningful way. And yet…there were times when it still felt like it had come out of nowhere.

The aftermath and forevermore

For the County, revenue recovery was a slow and arduous process.

- The first year in which income tax revenue exceeded FY07 income tax revenue was FY13, with the low coming in FY10 (FY10 income tax revenue was roughly 20% below FY07). Drags on income tax included the declining stock market, capital loss carryforwards, and unemployment and underemployment.

- Transfer taxes hit their low more quickly – in FY09 – but remained below FY07 levels for the next decade.

- Assessed values of real property increased through FY10, and then were up slightly in FY11 before falling below FY10 levels for the next 4 fiscal years. This delayed reaction was a function of the triennial assessment cycle, the state’s “circuitbreaker” credit which limits increases in any year to 10% and then phases in the excess, etc. By my count it wasn’t until FY16 (SERIOUSLY!) before assessed values exceeded those from shortly after the real estate crash.

- As a result of the County’s close call in 2010, new fiscal policies were developed to enhance the County’s reserves and the result included funneling hundreds of millions of dollars into the County’s general fund undesignated reserve and the “revenue stabilization fund.” These actions were essential for providing comfort to the rating agencies, but also to ensure that the County was able to stand by its commitments to residents, businesses, and the County’s workforce.

- These pressures made it difficult to “feed the beast”, which led to a decision to increase property taxes above the so-called charter limit; an indirect result of that budgetary decision was voters passing term limits for county elected officials.

- By the time most revenues had recovered, the Council and Executive were forced to agree to new savings plans as revenues once again were falling short of projections.

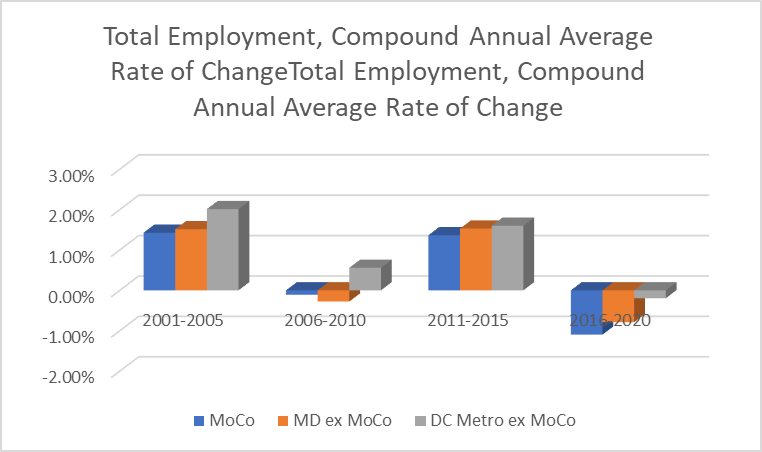

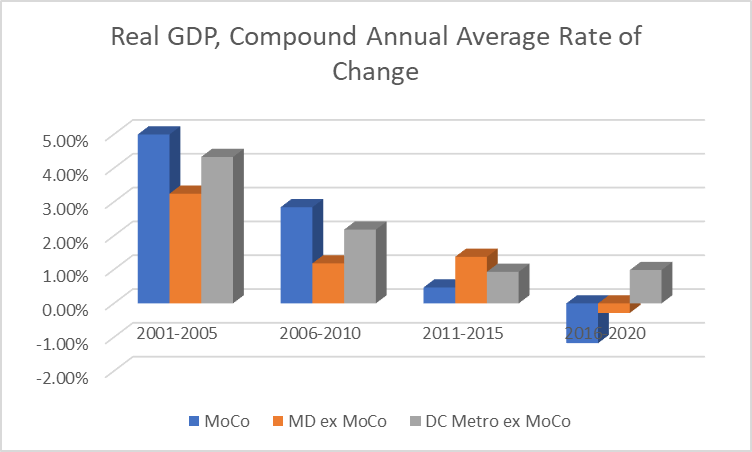

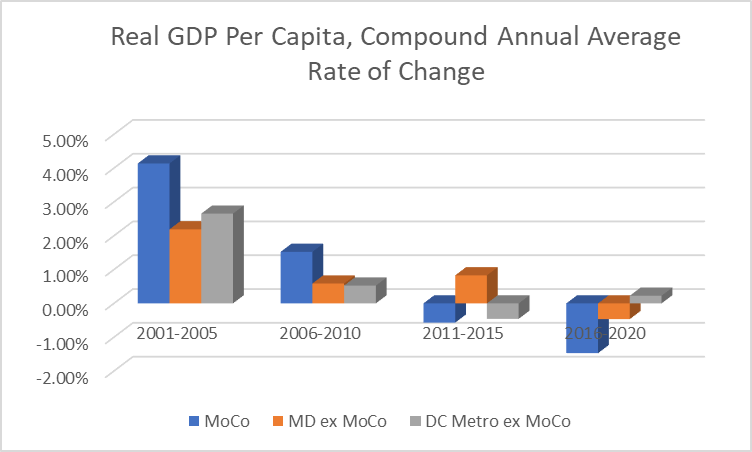

And the County’s economy was hobbled to such a degree that it really hasn’t recovered.

Furthermore, some of the specific industries most affected by the last recession have had a rough go of it ever since. I took a look at some of the local competitive effects back in February, but I can highlight the important take aways for those of you have made it this far: in 2020 the County was about $12 billion in GDP below where it would have been if each industry had performed as it did elsewhere over the previous decade, and 85% of that is attributable to the underperformance in finance, insurance, and real estate. Similarly, if employment growth in each local industry had kept pace with national growth rates, Mo Co would have had 40,000 more jobs in 2020 than it did. What portion of those were specifically attributable to underperformance in finance, insurance, and real estate? 60%, or 24,000 jobs. So, while we can’t say for sure what role the Great Recession had on those industries locally, or why those industries didn’t bounce back in Mo Co the same way they did elsewhere, we can say for certain that some of the industries most affected during the last recession have really had a rough go of it in Mo Co ever since.

Might this next recession play out differently?

The next recession will undoubtedly play out differently. It may not be as long, or as deep. On the other hand, it may turn into decades of stagnation in the US economy (à la Japan). But this next recession will occur in a Mo Co that is not as strong economically as it was when the Great Recession hit.

- Wage and salary employment has largely been flat or falling in Mo Co for years.

- Government employment and procurement has not been an effective driver of local economic development and is no guarantee.

- Household incomes and consumption have not kept pace with other portions of the region, in part because Mo Co has captured such a large share of the region’s low-income households, and goods inflation and pandemic era public health rules are putting local retailers in a vice.

- Manufacturing in Mo Co, while relatively successful, is a small part of the economy and is running out of room.

- High taxes, relative to Mo Co’s neighbors, deter private sector economic activity and investment…and this year’s compensation increases will be a “gift that keeps on giving.”

Many of the industries most likely to be affected are the same ones that were affected in the Great Recession. Construction, finance, and real estate are all highly sensitive interest rates (utilities and manufacturing might fall into that category as well). Of course, as incomes fall then so too does consumption…so retailers are always on the hook. Hospitality certainly could suffer if business travel again slows to a trickle.

From a fiscal standpoint, the “elephant in the room” is the possible impact of the recession on an already ailing office market, and subsequently on the values and tax revenue generated by office properties. There is already concern about the impact of work-from-home on office values in Mo Co, given that by my estimate 40% of Mo Co office jobs can be done entirely from home and given this recent study suggesting that WFH could result in a 40% hit to urban office values. Add to that a recession, which will prompt even more businesses to carefully evaluate the value of their leased and owned space…and who knows?

One thing that is unlikely to play out differently is the slow burn of the recession’s impact on the ability of local government to maintain services and balance the budget. What has not changed is that is hard to know in the moment whether you are at the beginning of end or the end of the beginning. What has not changed is that there are multiple factors that can lead to a situation in which the broader economy is in the tank while, simultaneously, local revenues look fine. What has not changed is that there are other factors that can lead to a situation in which the broader economy is recovering while the revenue picture just keeps getting worse. Let’s hope they have some dry powder left when The Big One hits.

I’ll be back later this month with a Flotsam and Jetsam. Until then, duck and cover, my friends!