The County’s slow-mo economy and structural challenges take center stage in this month’s flotsam and jetsam. DYK that over the past decade, proprietors’ income in the County has dropped by an average of nearly 2% per year and the income from welfare and social assistance programs has increased by more than 8% per year? Yikes. And after hearing a lot of confused comments about public sector spending in MoCo, we review some of the important public sector data sets and what they reveal about MoCo’s sources and uses of funds.

NEW 2020 PERSONAL INCOME DATA RELEASE

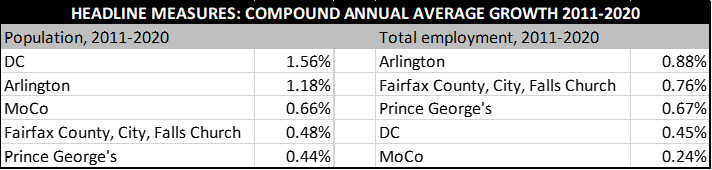

On November 16, the Bureau of Economic Analysis released 2020 personal income data at the county level. The data shows that Mo Co per capita personal income ↑3.86% from 2019 to 2020. While nowhere near the increases of a couple of area jurisdictions (Prince George’s County ↑8.51%; the District ↑7.11%), it was a larger increase than in two nearby Virginia counties (Fairfax ↑3.42%; Arlington ↑2.76%). Furthermore, the 2019-2020 change in wages and salaries was middling (↑2.53%), which counts as good news when compared to the Prince George’s County (↓1.02%) though it trailed the more robust increases across the river (↑4.25% in Arlington, ↑3.24% in Fairfax). Taking the longer view into account, I calculated the compound annual average changes in several key categories. First, let’s start with two big ones – population and total employment.

As anyone who has ever had to sit next to me at a dinner party knows, it is much more expensive to serve residential growth than commercial growth. And generally, large jurisdictions want to achieve a modicum of balance between the two. Over the last decade though, Montgomery County is gaining residents at a rate of 0.66% per year and gaining jobs at a rate of only 0.24% per year. That’s not a sustainable trend because services such as public K-12 education are really expensive, whereas the services that specifically benefit businesses are relatively speaking less common and less expensive. And the gap between our job growth rate and the job growth rates in Arlington and Fairfax are really big (their job growth rates are roughly 4x and 3x the Montgomery County job growth rate).

But, let’s face it, nothing new there…So let’s have a peek at the last decade of personal income data…

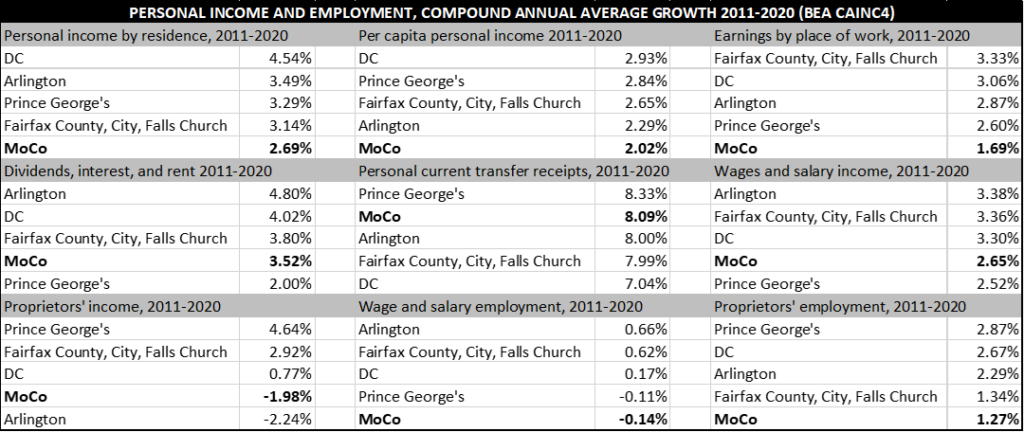

A few things worth noting in this data:

- The one category that you don’t want to excel at is personal current transfer receipts – basically, social welfare payments. Unfortunately, that is the category of income in which the County has “performed best” relative to neighboring jurisdictions – not really a sign of strength in the local economy. Generally, recipients of current transfer receipts pay little to no taxes, especially given Maryland’s progressive income tax structure, so this is not a sign of fiscal strength either.

- Generally, MoCo relies more than most area jurisdictions on proprietors’ income as well as dividends, interest and rent. While MoCo is “overweight” these two categories of income, as you can see the growth rates in both categories trail most of the competition, and on the proprietors’ income the average annual change is heading the wrong way (↓1.98% per year).

- You are reading that correctly – wage and salary employment has declined over the past decade (↓0.14% per year). Obviously, this is a bad sign in terms of the economy. It’s a bad sign from a fiscal standpoint as well, because wage and salary income is the stable part of any income tax revenue stream whereas year to year fluctuations with other forms of income present real challenges for fiscal planning.

WHAT PUBLIC DATA SAYS ABOUT THE PUBLIC SECTOR

In recent weeks I’ve had some frustrating conversations – with folks who should know better – about whether taxes are higher in Montgomery County than elsewhere in the region, or whether it is even possible to compare jurisdictions that are in different states. I think it speaks to how powerful the incentive is to just put blinders on and pretend like there isn’t a problem. All well meaning folks, but just plain wrong on this important issue.

Given that, I do think that it is worth reviewing the key public data that economists and policymakers use (or at least SHOULD use) in making apples-to-apples comparisons on this topic.

They count governments, too?

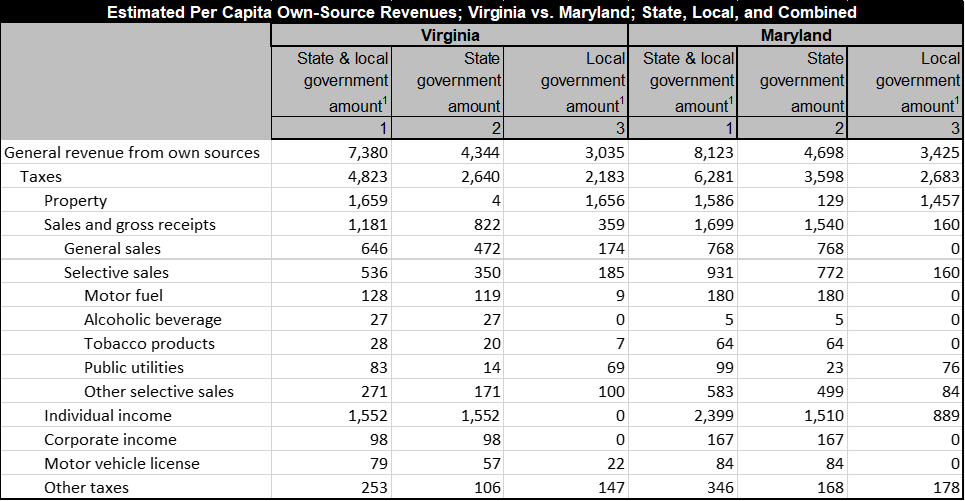

The Census of Governments should be the starting point for any such inquiry. The Census of Governments is literally an analysis of state and local government finances using a method that facilitates “apples-to-apples” comparisons. When I use the Census of Governments data, I usually normalize it on a per capita basis using the previous year’s population, which requires an extra step analytically but provides a much clearer picture than just looking at the gross numbers. Also, I really focus on the “own-source revenue” category, which excludes revenues like federal grants and transfers. One downside to the data is that it is not county-by-county – it is a state-based dataset that includes (separately) state and aggregate local government statistics. But if you know that Montgomery County is a high tax county relative to others in Maryland (it is) you can still draw conclusions from the data that are relevant to any discussion of state and local tax burdens in MoCo.

On a per capita basis, state and local government own-source revenues in Maryland are 10.1% higher than in Virginia. This means that state and local governments are raising 10.1% more money per resident (from all private industry and household sector taxpayers). Local governments in Maryland raise 12.8% more own-source revenue than their Virginia counterparts.

Obviously, a huge part of that is the local piggyback tax, which does not exist in Virginia. Clearly, you can’t look at the difference between Maryland and Virginia without acknowledging this key distinction. In fact, the amount of per capita individual income tax revenue is almost identical at the state level (actually, it is somewhat lower in Maryland than in Virginia), but the difference between $0 at the local level in Virginia and whatever it is in Montgomery County is huge (and by the way, Montgomery County’s number would be almost twice as high as the statewide average of $899 per resident). Of course, site selectors and commercial brokers are aware of this difference and are advising their clients accordingly.

The dataset isn’t limited to government revenues – it also addresses the expenditure side of the equation. In terms of current operations, on a per capita basis Maryland state government spends 14.1% more than state government in Virginia. That difference is even larger at the local government level – local governments in Maryland spend 17.9% more on a per capita basis than local governments in Virginia. And of course, a big part of any local government budget is compensation and benefits – governing is a labor-intensive enterprise, with a lot of dedicated people doing really important things. But that labor is also very expensive – at a local government level in Maryland, the per capita cost of salaries and wages is 19.2% higher than in Virginia. That’s a big number.

The differences don’t stop there – state and local governments (combined, per capita) in Maryland spend a lot less on construction and capital outlays than state and local governments in Virginia and a lot more on social assistance and welfare programs (about 50% more per capita, in fact).

None of this is to say that the services provided by state and local governments in Maryland aren’t important – they are – its just not spending that is likely to affect business location decisions. If anything, it is much more likely to affect the residential locations of low-income households who will benefit from a robust social safety net.

Drilling down a bit more on compensation and benefits

When talking to folks about operating expenditures, it often becomes apparent that many people are talking about the issue without knowing that there is an American Survey of Public Employment and Payroll (ASPEP). It is a great dataset, and the data is available at the level of each individual governmental unit and for a variety of sub-classes of public employees. And generally, the data confirms your suspicions about the overall picture – for example, Fairfax County has 17.7% more full-time employees than MoCo, yet MoCo manages to spend 4.7% more than Fairfax on full-time payroll. It shouldn’t be necessary to pay THAT much more than our next-door neighbors to attract comparable talent. I think we can all acknowledge that it is a complicated issue, that there is some nuance, and that at the same time it is possible to conclude that MoCo pays a lot – and probably a lot more than is necessary – to its public sector employees.

Obviously, BLS and BEA data tell a similar story. However, sometimes it can be harder to clean out the noise with those data sets (e.g., you might have local government employees who live in one county and work in another). In the BEA data, two data sets that one can look at are Total Full-time and Part-time Employment (CAEMP25N) and Compensation of Employees by Industry (CAINC6N). Compensation per full and part time state and local government employee in MoCo is 14.7% higher in MoCo than in Fairfax County, and grew more from 2019 to 2020 (↑8.4% in MoCo versus ↑7.2% in Fairfax). Of course, the experience for individual employees will vary quite a bit based on their agency, service area, and bargaining unit, but this general data helps paint the picture.

Again, none of this is to say that the County’s work force isn’t doing great and important things, or that public sector employees should not be valued. However, an awful lot of growth in the commercial tax base is needed to make that kind of compensation sustainable, and MoCo isn’t experiencing growth in the commercial tax base. Earlier this year I estimated that if MoCo had continued to capture its pre-2007 levels of jobs by industry, annual tax revenues would be $37 million above current levels. That would go a long way to making public sector compensation and benefits more affordable.

Killing the golden goose

The Bureau of Economic Analysis has some good GDP datasets to use when looking at the overall cost of doing business in a state – two I like to look at are SAGDP5 and SAGDP6. These datasets address the taxes on production (including taxes property taxes) and subsidies for production. Together they provide a good measure of “net taxes by industry.”

Taking a quick look at the 2020 update, one thing that jumps right out is that compared to earlier years, the subsidy levels are approximately 20x the annual average from before the pandemic. Clearly, 2020 is skewed by this increase and not representative of the longer history here. Looking back at 2019 (and the years before that), a key takeaway is that the issue appears to be less about taxes on the real estate industry – overall, net taxes on real estate are actually lower in Maryland than in Virginia – but more about the taxes on the industries that real estate needs as tenants in the DMV region.

Net taxes are higher in Maryland than in Virginia for several key industries, and lower in a few as well. But the real story here is our old friend Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services. Overall, the industry is just under a fifth of the Mo Co private sector economy and employment. And in terms of employment, it is the largest industry in Mo Co and the number one driver of the area office market. For that industry, net taxes as a percentage of GDP are 3.11% in Maryland, compared to 1.93% in Virginia (2019). To put that in perspective, using the 2019 data state and local governments in Maryland would need to reduce taxes or increase subsidies by $511.5 million to equalize the net tax situation in Virginia. No wonder Virginia is eating our lunch.

Similarly, the information industry, which includes a lot of data and data processing, is one that the county has really struggled in over the past decade-and-a-half. That struggle is apparent both in terms of jobs that left the county, and in the county’s poor performance in terms of attracting companies in the industry. The net taxes in Maryland are 4.12%, much higher than the 2.47% of GDP in Virginia. Again, using 2019 data the difference from a net tax standpoint is substantial. Eliminating that gap would require Maryland state and local governments to reduce taxes (or increase subsidies, or both) by $245.7 million.

Just a point of emphasis – these are the two industries that include most of the jobs in government contracting, bioscience, and technology. So, basically, all the things MoCo wants to be good at and that are driving the current and future office market.

These examples get to one of the big reasons that I recommended establishing a large incentive fund for Montgomery County that would both target potential office tenants by providing a per job grant, and also reduce the cost of leasing by providing grants to offset some of the cost of tenant fit-out (which either needs to be paid for up-front, or gets amortized into the lease rate thereby becoming part of the rent). We need to offer incentives to tenants directly, and we need to help commercial property owners incentivize occupancy by reducing the overall costs to the tenant. Lower rents on Montgomery County offices will help offset higher net taxes on production in key industries. We aren’t competing without them, and we need to get serious about competing right now.

MoCo needs to be a more attractive place to companies on the move. Those companies do not view Montgomery County as a cost-competitive location. And the County needs them to take a more favorable view of locating in MoCo because it isn’t clear where the tax revenue is going to come from to provide a high level of services to an increasingly unequal and needy population – or compensation increases for County employees – without having a strong commercial property base.

Finally, to those who want to dispute the data and the existence of the problems, I pose this question: if the decisions to locate elsewhere don’t have anything to do with the cost of doing business, then what does that say about how unfavorably businesses and real estate developers view MoCo? The question is irrelevant, because in fact the cost of doing business in Maryland IS higher than it is Virginia. We should be focused on mitigating that problem, rather than denying it. Nevertheless, it is a question worth asking anyone who tries to sell you on the idea that the way the County raises and spends money isn’t related to the County’s current position at the back of the regional pack when it comes to growth and development.

WRAPPING UP

I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with more data, including a review of the soon-to-be-released GDP figures for D.C. area jurisdictions. Until then…stay safe, be well, and shop MoCo!