In this latest installment of Mo Co Economy Watch, I address some odds and ends: ranking the retail submarkets; estimating the share of the daytime population that can work from home; and looking back at WARN notices during the COVID-19 recession.

Retail submarket rankings

We wrote recently about Montgomery County’s current/recent struggles to generate retail sales at a level that matches past performance or nearby jurisdictions. I thought it might be fun to take a quick peak at how our retail submarkets are performing relative to other submarkets in the region. The advantage of looking at the submarkets rather than examining the County as a whole is that economic activity doesn’t really recognize political boundaries. As a result, submarket boundaries tend to be more relevant to the way that economies actually function (even if they are sometimes less relevant to the public policies that affect local and regional economic activity).

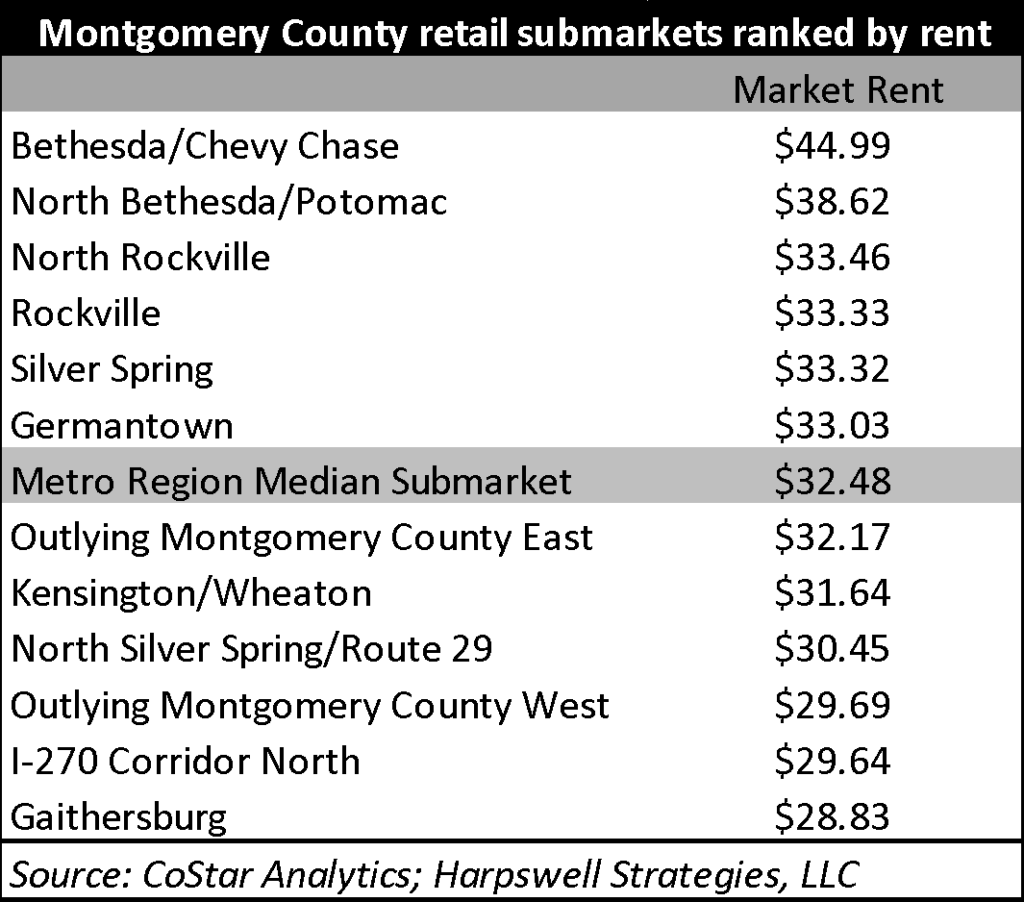

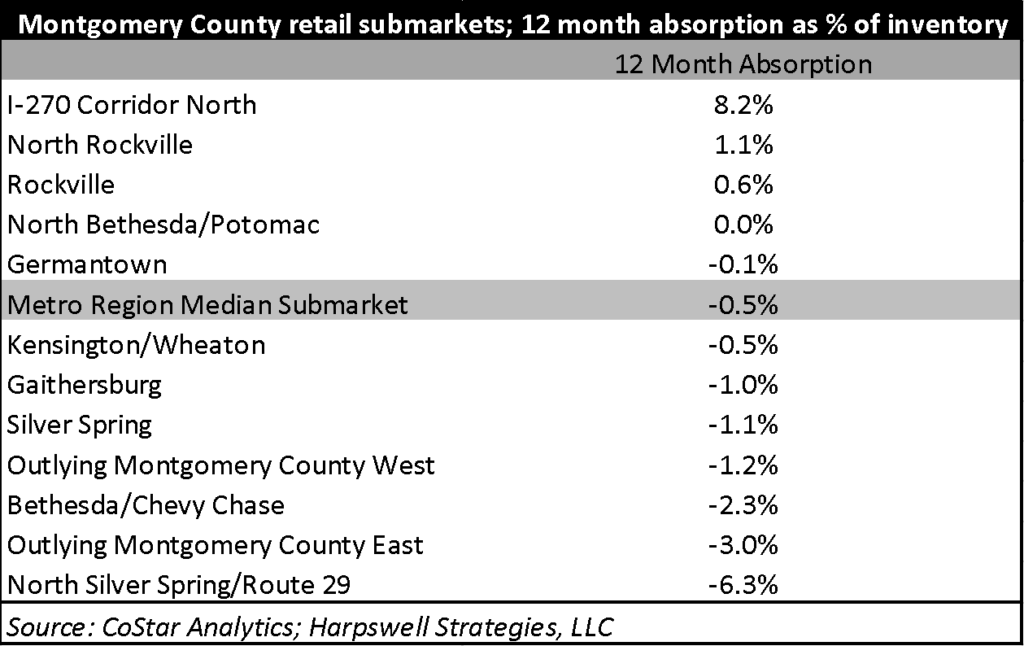

First, let’s take a look at the retail submarkets by rent and compare those against the median submarket for the DC region.

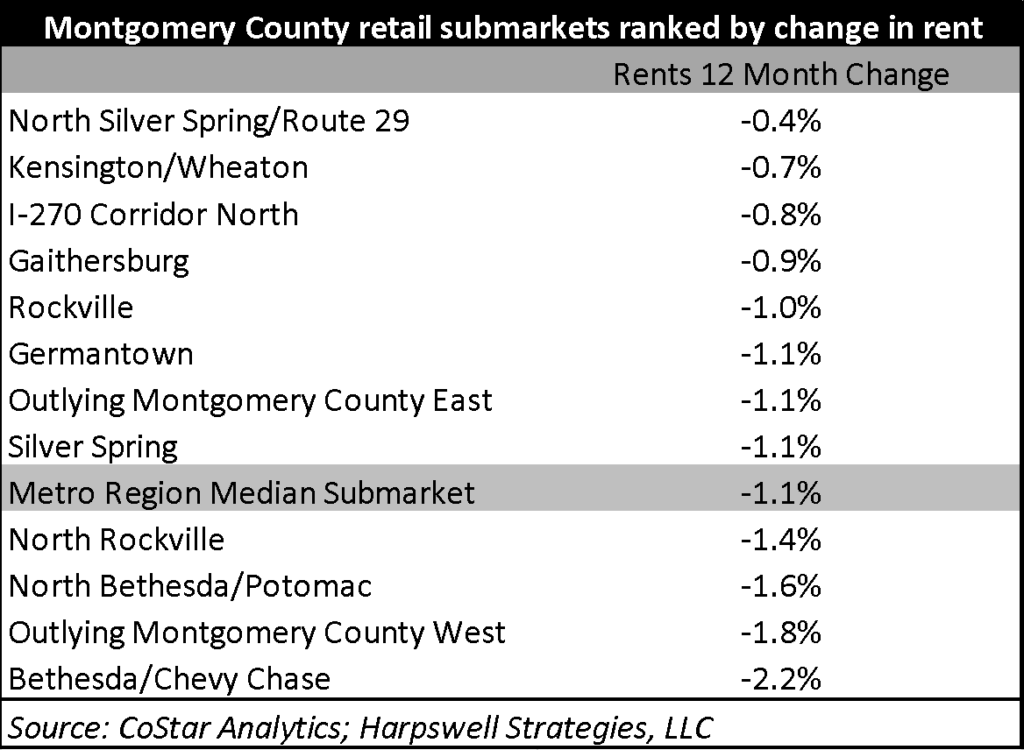

It is not surprising to see which submarkets are on top or how much separation there is between #1 and #2, and between #2 and everyone else. What is somewhat surprising is to see how much those more expensive retail submarkets have been affected by the pandemic relative to the other submarkets.

It is a surprise to see how poorly the Bethesda/Chevy Chase submarket has performed, but it is also surprising to see such a clear geographic divide, with the westerly submarkets underperforming not only the other submarkets in the County but also the median submarket for the entire region.

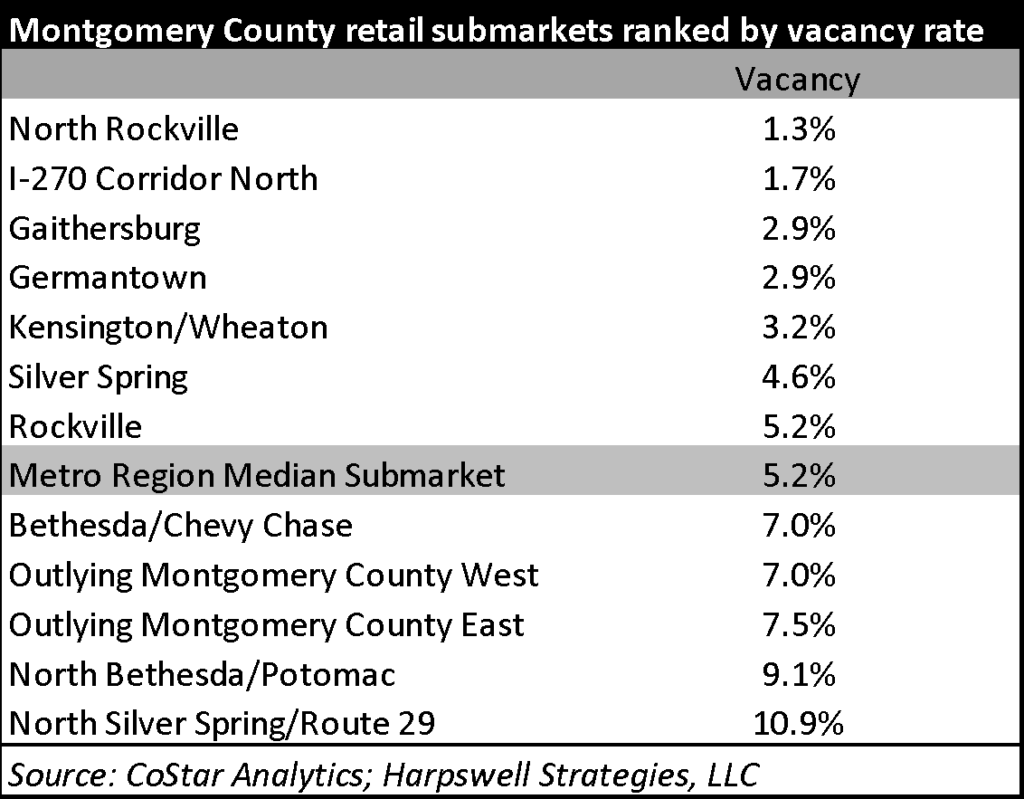

The vacancy rate for the entire region is 5.2%. In large part as a result of the fact that very little new retail space has actually been delivered in the County, the vacancy rates in most submarkets are actually below that level. Again, though…there are some troubling signs in the numbers for Bethesda/Chevy Chase and North Bethesda/Potomac insofar as those retail vacancies are sitting on valuable land and are expected to do a lot of the heavy lifting for Mo Co retail sales and commercial property values.

Looking at the 12-month change in vacancy rates, we can see some outliers – I-270 North (which includes a bit of Frederick County as well) had significant positive absorption (a lot space taken up and leased) and North Silver Spring/Route 29 had significant negative absorption (a lot of previously occupied space that is no longer occupied).

From a fiscal and economic development standpoint, I’m really focused on two numbers in the table above: Bethesda/Chevy Chase again is in the bottom half of one of my table, and so is Silver Spring. Bethesda is surprising for so many reasons (it is part of a relatively large office market, it is close to the District, there is a ton of disposable income, and the environment is really pleasing – I mean, you can literally walk across Wisconsin Avenue there without being terrified and how many places like that are there?). Silver Spring arguably represents the only long-term economic development success story in the County insofar as literally hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent on major infrastructure and community facilities/amenities, reducing taxes, facilitating development, incentivizing employers, etc.

I’ll be keeping an eye on Bethesda/Chevy Chase to see how the return to offices affects the health of the retail there. In contrast, however, with Discovery Communications now in NYC and other locations it isn’t obvious where the upside will be coming from in Silver Spring. We need some downtown employers there to give that submarket a boost.

Working from home, wherever that may be

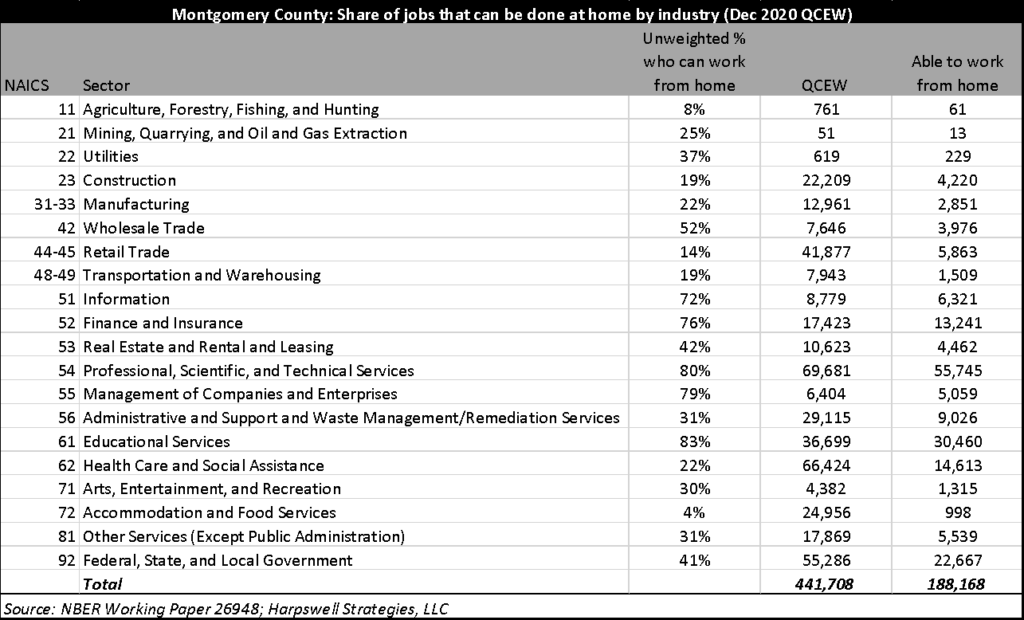

The effect of work-from-home on local economies will, of course, vary with the degree to which the local workforce engages in occupations that can be performed from home. One recent study (Dingel and Neiman, 2020) estimated that “37 percent of jobs in the United States can be performed entirely at home, with significant variation across cities and industries. These jobs typically pay more than jobs that cannot be done at home and account for 46 percent of all US wages.”

I thought it would be interesting to apply some of Dingel and Neiman’s findings to Montgomery County and see what portion of those who work in Montgomery County might be able to continue to work from home. I limited my analysis to “covered employment” which means that I excluded some categories of jobs like farm and non-farm proprietors, a large portion of whom can work from home in their capacity as proprietors, but some of whom might have other employment. The “covered” part refers to unemployment insurance – “covered employment” is basically the universe of people who work for other people.

There are two reasons that I have been interested in this data (and the reason why I approached this question from the “covered employment” angle).

- I am eager to get a handle on what portion of the workforce we can reasonably expect to return to the office as a way to better understand the new normal in retail and food service demand in the County’s commercial districts.

- I am really curious about how work from home (and especially the likely prevalence of hybrid work from home over the next year) is going to affect energy consumption in the commercial sector, the residential sector, and total consumption of electricity. My guess is that as some people return to work, electricity consumption by commercial customers will approach the pre-pandemic normal, while residential consumption of electricity will remain elevated. I don’t think there is any question that this will result in more electricity being consumed, but how much and in what proportions has implications not only for greenhouse gas emissions but also, more provincially, on County fuel/energy tax revenue.

This what I came up with when I matched Dingel and Neiman’s findings by two-digit NAICS code to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages data for Montgomery County (December 2020). Based on this approach, 42.6% of Montgomery County based jobs can be done at home.

Worker Adjustment and Retraining and Notification Act filings in the era of COVID-19

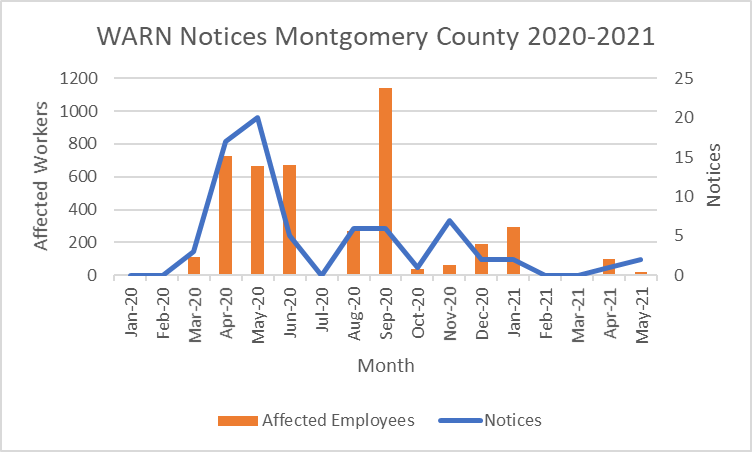

WARN notices are a useful real-time source of economic data. The Worker Adjustment and Retraining and Notification Act requires certain large employers, under many circumstances, to provide 60-days notice of any plant closure or force reduction affecting more than 50 employees. For a full explanation of who is required to file a WARN notice and under what circumstances, check out the Department of Labor’s explanation and the FAQs that DOL posts for those interested in learning more. The long and short of it is that the data are not equivalent to unemployment numbers, and do not represent the entire universe of layoffs. They are useful during periods of recession, however, because the filings are posted in real time before other data is available for analysis.

In Maryland, WARN notices are posted by the Maryland Department of Labor. I peeked at the data recently just to see what it tells us about the pace and scale of the recovery. The data tell a story that will surprise no one – mass layoffs were mostly in retail, restaurants, hospitality, and health care industries. There are relatively few outliers, such as BioReliance notifying 99 workers of an impending force reduction in late April of 2021. And there are a few outliers that are hard to categorize, such as WMATA’s notice to 1100 to 1200 area workers in November at 11 sites in the region.