In this MoCo Economy Watch, we try to untangle a gordian knot – the relationship between the local economy and government taxing and spending. Local taxing and spending do impact local economic performance. Today we’re going to dig into the literature and explore how and why that happens.

local taxing and spending decisions actually affect the local economy

St. Louis is an example of a jurisdiction that has fallen victim to its own taxing and spending. St. Louis “went south” pretty quickly in the last century. The following summary, taken from Robert P. Inman’s instructive piece Financing Cities, appeared in Blackwell’s 2008 book, A Companion to Urban Economics.

“…In 1952, St. Louis had 51 percent of the region’s employment within its borders. Today, only 12 percent of area jobs are in the city. Over the past 50 years, the suburbs have been gaining jobs at the rate of 2.7 percent per year, while the city has been losing jobs at the rate of 1.7 percent per year.

“What happened? St. Louis’s decline was, to an important degree, a product of its own doing. City public spending per resident in St. Louis rose at an annual real rate of 3.4 percent over the period from 1955 to 2000, compared to a national average rate of growth of 2 percent for all large US cities…The causes of high city spending were high growth rates in public employee compensation and a rising ratio of public employees to city residents. Growing city poverty played a role too. Facing a potentially significant gap between taxes paid and services received, it is not difficult to see why the middle class and businesses stopped ‘meeting in St. Louis.’”

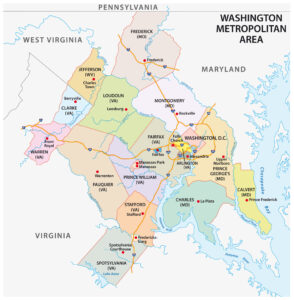

Montgomery County’s current situation is different from the situation facing St. Louis in the mid-20th century, but some commonalities are evident (e.g., high taxes, high levels of public employee compensation, reduced quality of services, capital mobility, and a declining share of regional employment).

Professor Inman, a top expert in the fields of political economy and public finance, goes on to describe the kinds of taxing and spending that promote economic growth and those that stifle growth.

“…[F]or any city to realize its full economic potential, the efficient provision of city-specific infrastructure and public services is essential. City firms need roads, bridges, telecommunication networks and city residents need education, safe streets, and clean and healthy environments. These are the tasks of city government. Efficient city finances will require, first, an appropriate assignment of spending and taxing powers and then, second, a structure of city political institutions and rules of governance to insure [sic] that these assigned powers are used to maximize resident welfare and firm profitability…

“What public services should the efficient city government provide? Successful cities require public services and infrastructure that complement private capital and labor in production and create physical and social environments valued by the cities’ residents. Among these services, city governments should be limited to financing those with spatially confined spillovers…Services with significant spatial spillovers should be financed by higher levels of government…What city governments should not do, at least from their own tax resources, is redistribute incomes. Mobile upper-income households and businesses will simply leave the city, and in the process undermine city agglomeration economies and then finally city economic efficiency. Poverty services should be financed at least at the level of the metropolitan area, and more ideally by state or national governments…”

And Professor Inman is not alone in this view that local anti-poverty programs that lead to tax increases often exacerbate the concentration of poverty and compromise the ability of cities to maintain current levels of investment or prevent the flight of capital. For example, economists Ross Gittell and Edinaldo Tebaldi have extensively studied issues related to metropolitan area economies and have focused a lot of attention on the issue of poverty persistence. And, like Inman, they have found that a portion of the problem of poverty persistence in metro areas is that efforts funded by local tax dollars do not do enough to offset the negative impacts of increased middle class and business tax burdens associated with funding such programs.

In one study Gittell and Tebaldi conclude, based on empirical analysis, that addressing the needs of impoverished residents with high levels of public services funded by relatively high local tax burdens can be a risky poverty reduction strategy. Like Inman, they find that increased taxes to fund social services has a detrimental impact on overall growth, which can contribute to the persistence of poverty in local areas. What is the mechanism? Research indicates that this can happen when high levels of public social expenditures require relatively high property tax burdens, corporate tax burdens, and sales taxes; these tax burdens lead to decreased investment, discourage economic activity, and contribute to the flight of mobile capital.

As a brief aside and preview to another piece I’m working on this spring, some of the actions taken since 2007 include Maryland’s decision to increase the corporate tax rate from 7% to 8.25%, multiple local property tax increases, a massive increase in the county’s fuel/energy tax that was supposed to sunset after 3 years, and increased inclusionary zoning requirements in much of the county. Spoiler alert – the combined impact of those decisions and others has been, you know…decreased investment, reduced economic activity, and the flight of mobile capital…

some kinds of spending are better than others

Inman provides a good framework for thinking through the issue of how an efficient city should function, but given that some of the spending is in the form of borrowing, what we need now is a very simple explanation of how credit and debt works. For that, I turned to Ray Dalio’s book Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises.

“…Generally speaking, because credit creates both spending power and debt, whether or not more credit is desirable depends on whether the borrowed money is used productively enough to generate sufficient income to service the debt…”

Here, Dalio has gotten straight to the point. “Borrowed money” should be used to productive ends in order to make it worth the cost, and as will be discussed at greater length below, borrowed money includes borrowing from our future economic productivity to meet current demand, underfunding ongoing costs like maintenance and pensions and retiree health benefits, etc. At a minimum, enough of the borrowed money that is programmed must generate future economic growth that can support the cost of all moneys already borrowed. Dalio goes on to explain the mechanics:

“…Buying something you can’t afford means spending more than you make. You’re not just borrowing from your lender; you are borrowing from your future self. Essentially, you are creating a time in the future in which you will need to spend less than you make so that you can pay it back. The pattern of borrowing, spending more than you make, and then having to spend less than you make very quickly resembles a cycle. This is as true for a national economy as it is for an individual. Borrowing money sets a mechanical, predictable series of events into motion.”

Of course, this is as true for metropolitan economies and local jurisdictions as it is for the national economy and individuals. And just as it might make sense to pay monthly debt service on a vehicle that allows you to get to a job at which you expect periodic salary increases, it might make sense to borrow public funds to build road capacity or invest in public facilities that, over the next several years, will result in increased private sector (taxable) economic activity. And just as it didn’t make sense back in the mid-aughts when folks were taking out home equity loans to purchase large TVs, there are a lot of public sector expenditures that do relatively little to change private sector economic activity or public sector revenue over the long-term.

This is simply to say that there is a danger in shifting too much “spending” to areas that are unlikely to generate increased private sector, income-producing activities. Below are a couple of examples:

- If office workers stop taking the train and bus to the office, then is borrowing money to build another transit option (e.g., bus rapid transit on MD 355 South) going to lead to long-term economic growth that justifies the debt we’ll be carrying on our books? What is the new private investment or taxable economic activity that would be spurred by having an additional transit option on that stretch of the Pike?

- If our greatest affordable housing need is for very low-income individuals, and if we assume that most very low-income individuals currently lack the skills necessary to work in knowledge-based high-value jobs, then what is the mechanism through which increasing the population of very low-income households and individuals will lead to future economic growth or economic activity that creates public sector revenue? And how much future revenue (property tax, income tax, etc.) can we lose, and service cost (social safety net) can we provide, for the benefit of residents of each inclusionary zoning unit for the county’s 99-year control period?

This isn’t to say that MoCo shouldn’t strive to provide transit services to those who by choice or by necessity choose to live without a car, or that the county shouldn’t strive to house those who cannot afford to house themselves. It is simply to say that sometimes half a loaf is as much as we can afford. And when we think about what it means to “be able to afford it,” we do need to acknowledge that actions taken today do affect current and future levels of economic activity and the potential for that economic activity to generate revenue, and that we aren’t just talking about the county budget but also the productive capacity of the land in Montgomery County.

How much will MoCo borrow from the future (in terms of debt service, future profitability and taxable value, etc.) to address the current and near-term housing and transit needs of its vulnerable residents? And under what set of assumptions can we afford to do so for the foreseeable future? I think it should be possible to agree that (a) there is a moral cost associated with not addressing these needs, and (b) that MoCo has to actually be able to afford (economically, financially) to do so both in the short run and in the long run.

If MoCo is going to invest significant amounts of resources in services that are unlikely to generate future growth, it is fair to ask what source of growth is expected to drive future revenue growth. My guess is that the answer is dogmatic magical thinking, i.e., that if county political institutions implement as many progressive priorities as quickly and completely as possible, all the rest of it will take care of itself and future MoCo residents will live in perpetual felicity, free from want and free from having to compromise with those who don’t vote in off-year party primaries.

what i mean when i use words like taxing, spending, credits, and debts

Long-time readers already know my take on this, so I’ll keep it short. When I use these terms, I use them according to their economic meanings. For example, inclusionary zoning is a tax (as are the county’s ag land preservation zoning requirements and temporary rent control) imposed on real estate entities and real estate investments for the benefit of a part of the public. Similarly, some spending is also off the books – private sector production of required low-income units is a form of public spending – it isn’t the kind of spending that occurs when county funds are used, but it is a reduction in the productive value and hence assessed taxable value of the land. Similarly, the credit on MoCo’s books is one less affordable unit demanded (theoretically) while the debt is perhaps lost future economic and revenue impacts of market rate housing and the tax value associated therewith.

Other examples abound, but I would say that unbalanced budgets represent borrowing from tomorrow for the benefit of today, as do the following: fee and user revenue transferred to the general fund; underfunding of pensions and OPEB obligations; underfunding of “level of service projects” and routine maintenance, etc.

effectiveness and appropriateness of local government efforts to address national problems

As the local media has declined, local voters have become less informed on local issues and politics. Partisanship has also become the strongest social force shaping our identities, such that any local voter may feel that all they need to understand about a local politician is where they stand on specific national issues (immigration, health care reform, etc.). And a result of these two trends is that local elected officials are increasingly campaigning on and accountable for their views on issues that really aren’t local government issues, per se. And of course, one issue with a local campaign on national issues is that local governments can’t deficit spend…so there is a real disconnect between the way progressive candidates and elected officials think and talk about spending on the one hand, and on the other hand what they can actually afford to implement with local resources.

I’m not going to dwell on the point, in part because I regard it as self-evident, but local governments are not well-positioned to address national or global problems. The reality is that spending so much effort and money trying to solve problems that are bigger than any local jurisdiction can address leads to a lot of wasted money and effort. Global inequality is a problem, but Montgomery County’s political institutions aren’t going to be able to swim upstream against that force. The global environment is in crisis, but there is a limit to how much any one of America’s 3,006 counties can do to address that.

Let’s face it: as a country and as a county we are challenged to have the hard “adult” conversations around the limitations of policy (my favorite national example is MMT – don’t get me started on this variety of magical thinking!). Locally, that plays out in an unwillingness to admit the limitations of trying to address global problems with local policies.

There’s no prize for doing the most in a losing effort…except maybe for the political campaigns who only need to convince a small slice of the electorate to show up and vote for them in off-year party primary. The electoral incentives are there for politicians to sell you a “we-can-do-it-all-and-anyone-who-tells-you-otherwise-is-not-as- pure-or-visionary-as-I-am” approach, and by the time anyone realizes that they were sold a bill of goods it will be too late to unwind the transaction. But that kind of thinking only does harm to the greater good.

Perhaps more to the point: there is no bottom to the needs in society or to the amount that could be spent to address current and historical inequities. Addressing any of these big societal needs requires resources – do our political institutions function well enough to ensure that we have the resources we need to meet basic needs and also to address some, but not all, of what we would like to do to minimize suffering and create a more just world? Or are we stuck in the land of no compromises, political hostage taking, and heads-I-win-tails-you-lose politics? And what does that mean for our long-term economic and fiscal health? Because there is no end to what could be spent to address some of these issues, and it doesn’t really matter whose money it is or whether it was appropriated during the budget process.

Wrapping up

The county’s policymaking institutions continue to push the county headlong into borrowing more and more heavily from the future to satisfy today’s impatient constituencies around specific issues like affordable housing, transit, and school construction. As such, the county runs a very real risk of borrowing so heavily from that future that it could find itself in a downward spiral that will require decades to unwind.

However, there isn’t much demand from policymakers for analysis of the fiscal and economic multipliers associated with that spending. And in this political environment, I’m not sure that there is much point to asking for more analysis anyway. Anyone who watches the county’s political institutions probably understands the degree to which “impact statements” (economic, environmental, equity, fiscal) have been or will be weaponized.

But leaving analysis aside, those decisions often get made without even asking the basic questions – questions like “how exactly is housing for very low-income households and individuals going to spur economic growth in a county that focuses its economic development efforts on its knowledge-based economy and highly educated labor force?” or “how exactly is an additional transit option on MD 355 South going to lead to the kind of economic growth that would justify the costs (of debt service, of disruption to transportation corridors, etc.)?” And yet we include affordable housing and transit in our economic development strategy…

It would be reductionist, and arguably immoral, to argue that every policy needs to create an economic benefit; and it also is reductionist, and arguably disingenuous and counter-productive, to argue that every policy action needs to advance every single progressive policy objective. We should be able to “do economic development” for economic development’s sake, and part of doing that is pretty easy – providing good public services in exchange for reasonable tax burdens. And when you have developed the economy, you might have some extra resources available to do the stuff that feels so good – making MoCo a more just and equitable place.

Instead, MoCo continues to borrow from future economic productivity to meet today’s policy and political imperatives (affordable housing, transit service, higher private sector wages, agricultural land preservation, school construction, etc.). And MoCo continues to do so without considering how or whether these policies will lead to future growth. And if those substantial investments do not generate future economic value, then where is that economic value going to come from? My guess is that MoCo will double down on what got us to this point – bioscience, proximity to the federal government, our highly educated workforce, etc.

If insanity is doing the same thing and expecting a different result, then is this a form of collective insanity? Over the last several years, the economic decline of the county has accelerated – a trend that I have been studying and documenting in these pages for a year – and yet, the pervasive myth of MoCo’s exceptionalism continues to lead its progressive policymaking institutions to recommend new ways to extract value from land and the means of production to solve societal problems that may not be solvable at a local level. I think the evidence is clear that there is no more juice to be squeezed, and that our new idea for sources of future economic and revenue growth is the same as our last idea, the results of which have been disappointing to say the least.

I’ll be back next week with something more quantitative. Until then…be well, stay safe, and shop MoCo.