OFFICE VACANCIES: NOT JUST THE OWNER’S PROBLEM

Each month I will cover a special topic relevant to the economic health of Montgomery County; this month’s topic is about our escalating commercial office vacancy rate and the very real and lingering effect it is likely to have on Montgomery County’s budget.

One of the things the COVID-19 pandemic has normalized is the work-from-home trend, which will put tremendous pressure on the County’s office market recovery. One economic study from last year projected that the share of working days that will not involve physical presence in the office will triple as a result of the pandemic. Obviously, a change of that magnitude would have a significant, long-term effect on office demand.

While a “healthy” office vacancy rate usually hovers around 10% – it was 9% in DC between 2014-2017 as new offices were being constructed – it is now much higher than that across the DMV. In fact, the office vacancy rate is nearly 20% in the Montgomery County multi-tenant office market. Trends point to further fallout once current leases expire and tenants are faced with post-pandemic leasing decisions.

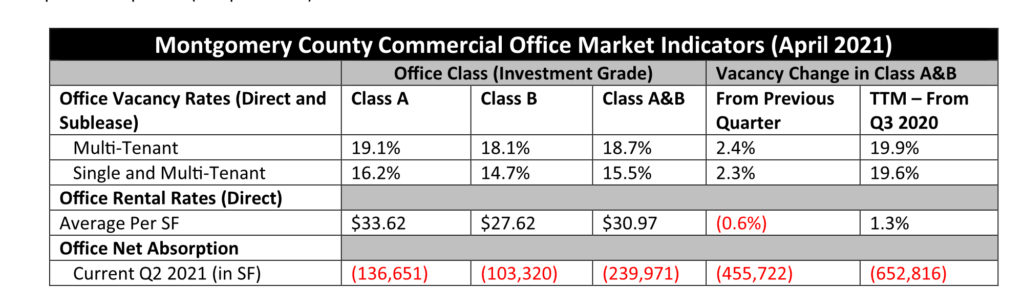

The table below presents key office health indicators in Montgomery County:

1.) Office vacancy rates (multi-tenant buildings in particular),

2.) Direct rental rates (not subleased rates), and

3.) Net absorption this quarter (in square feet).

While employment has partially rebounded from the depths of the pandemic, office vacancies went up and never came down. Vacancy rates have grown by nearly 20% since prior to the pandemic, as the County has shed over 650,000 square feet this past year alone (equivalent to about six large office buildings!) with potentially more to come. Even after the pandemic subsides, the increasing acceptance of telework and virtual technologies, greater cost sensitivity, and the changing nature of work suggest that lower office demand is here to stay (and by the way, such trends have been building even before the pandemic; COVID-19 only accelerated them!). Consequently, it may take several years before the region’s office supply and office demand stabilize.

Some may think that the office vacancy problem really is the really the owner’s “cross to bear”; perhaps market pressures can force owners to reduce rents? However, given that rents in the County are already well below those in nearby Northern Virginia and that office properties in the County already trade at a big discount relative to similar buildings across the river.

Some may also wonder why landowners can’t convert office buildings to different, more socially beneficial uses (like school buildings or affordable housing!). However, the enormous amount of capital required for redevelopment or conversion – which is further disadvantaged by slow employment growth in Montgomery County – means that property owners cannot do this on their own. This 2017 blog post from the Planning Department explores some of the issues associated with those conversions.

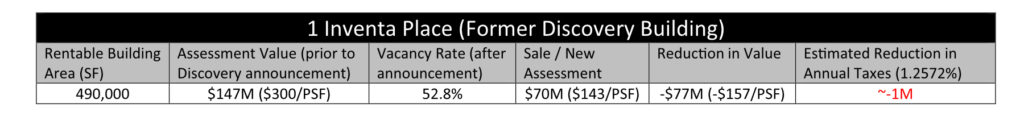

More likely, these buildings will continue to serve as offices but languish both in terms of rents and occupancy. Why is this important? Commercial real property taxes currently represent over 20% of County property taxes, which in turn represent about 46% of the County’s annual budget. Vacancies and lower rents reduce income to the buildings, thereby reducing the assessment values that are the basis for tax collection. Sometimes, this is reflected immediately, as was the case for the Discovery Building in Silver Spring. In January 2018, Discovery Communications announced they were leaving Maryland for New York. The building was sold in September 2018, and by July 2019 its office vacancies had already resulted in a valuation of the building that is less than half of its original assessment.

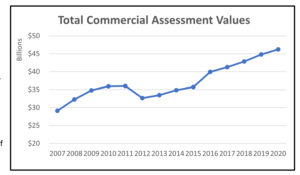

More often, due to the multi-year nature of commercial leases and the State’s triennial assessment cycle, reduced property assessments don’t result in immediate reductions in tax revenue. Those same factors also lead to really slow recoveries. This can be witnessed in the County’s uneven commercial assessment value growth since 2007 (for instance, we see assessed values climbing during the Great Recession, then dipping nearly 10% in 2012, a couple of years into the recovery). In fact, assessments of commercial real property remained below the 2011 level for the entire period from 2012 through 2015.

With structural changes to the office market and the impending office glut, no one should not be surprised to see commercial assessment values fall in the next few years. Problem is, in the past the County has had the freedom to increase the tax rate when assessments were down, so long as overall revenue collected was within the annual Consumer Price Index (CPI). If rates had remained at 2011 levels over the four-year period from 2012 through 2015, total cumulative property tax revenue would have fallen $521 million below actuals.

With structural changes to the office market and the impending office glut, no one should not be surprised to see commercial assessment values fall in the next few years. Problem is, in the past the County has had the freedom to increase the tax rate when assessments were down, so long as overall revenue collected was within the annual Consumer Price Index (CPI). If rates had remained at 2011 levels over the four-year period from 2012 through 2015, total cumulative property tax revenue would have fallen $521 million below actuals.

With the passage of the Charter amendments in November of 2020, the tax rate won’t increase unless its unanimously passed by all 9 (soon 11!) of its councilmembers. With a declining assessment base and the inability to equalize revenues by increasing tax rates, I do worry that Montgomery County’s going to be without an umbrella and hit by an economic storm of…dare I say…unprecedented intensity. I hope I’m wrong.

Looking at the bright side, it is possible that this Charter amendment will help elected officials to focus on assessments as a symptom of the condition of the economy, rather than simply relying on property tax rates as an automatic stabilizer. Hopefully, doing so will make it easier to control the costs of government, which are much higher on our side of the Potomac.

- According to the Census of Governments, Maryland taxpayers pay around 12% more per capita than their Virginia counterparts for state and local government.

- And based on the BEA’s personal income data, Montgomery County’s local government employees on average earn about 13% more than Fairfax County employees.

In any event, my guess is that the County will face substantial revenue pressures for several years and will do so now at a time when both the recent trend (Montgomery County underperforming relative to the region) and current fiscal context (less revenue flexibility than we had coming out of the Great Recession) represent significant challenges. Federal largesse will help close the budget gap, but the County’s “own source” revenues, such as the property tax, could suffer for several years. Office vacancies represent just one problem among many facing Montgomery County as we emerge from the pandemic-induced recession, but it is a big problem and one that could have a very long tail. Given the scale of the problem, mitigating the damage by stabilizing office occupancy will require bold policy interventions.

I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with an update on key economic indicators and a focus on employment statistics. Harpswell Strategies, LLC will be providing economic updates every two weeks for the next several months. Feel free to drop us a line and let us know what you think, and please forward to others who might be interested.

Kind regards,

Jacob